Historian and archaeologist Fabrizio Selli explores the history of dragons in the Western consciousness and in particular, their special connection with the City of London

by Fabrizio Selli

Living in today’s world, perhaps we don’t realise the importance of the museum. We take the existence of these institutions for granted – they have always been there, in our lifetimes at least. In the modern era, museums are available whenever we need information, or fancy having a closer look at a special object or work of art. Even with the invention of the Internet, museums are still extremely popular because they give the possibility to see wonderful things up close and personal.

Even in the 21st century, we still want to visit museums. We hope to find something unusual. We want to satisfy our curiosities, or perhaps we simply want to have a good time. Most likely, these are the same experiences that our predecessors wanted. In short, unusual things fascinate us.

Dragons have long occupied this space of curiosity. There has always been a conflict between science and popular belief regarding the existence of these creatures. Sometimes people exploring London are interested in the history of the Great Fire of London, and head to the Monument of the Great Fire of London – perhaps not knowing that they will encounter some dragons, too.

The Monument Dragon

If you have visited the Monument (designed by Sir Christopher Wren and Dr Robert Hooke and erected in Fish Street Hill between 1671 and 1677, to commemorate the Great Fire of London) you may have noticed that at its base we don’t have just one dragon, but four. They are sculpted near the base of this Doric column, which with a height of 202 feet is intended to represent the distance from its spot to Pudding Lane, where the flames of the Great Fire first appeared.

At the base of the Monument is a pedestal with some inscriptions and sculptures. A solo dragon emerges, carrying a breastplate with the City of London coat of arms. However, on top of the base, between the end of the column and the start of the pedestal, we find our four dragons.

Sculpted by Edward Pearce, the dragons are situated at each of the four corners of the monument. Alllegedly, they represent that they are protecting the city from any present and future calamity. We do not have much information on Pearce’s life, but do know that he was the son of a painter and a trusted collaborator of Sir Christopher Wren – hence the commission for this work on such an important landmark.

Unfortunately very few of Pearce’s works have survived, but apart from the Monument dragons we do have another remarkable work featuring a dragon: a wonderful wind indicator that Pearce designed for the church of St Mary le Bow in 1680, probably inspired by the Monument beasts.

Until the Great Fire in 1666, the majority of London printers and bookshops were based in the area of St Paul’s Cathedral, not far from the Museum of London. In 1607 a major work on mythical beasts was printed here: The History of Four-footed Beasts.

The author was Edward Topsel, as printed in the frontispiece of the book, though later he has come to be referred to as Edward Topsell. He was an English cleric for the Church of England from Kent, and managed the parish of St Botolph in Aldersgate from 1604 until his death in 1625. He definitely was not a naturalist himself, and his works were clearly derived from the authority of earlier works.

Then, in 1658, Topsel’s first book was reprinted together with another of his works on serpents, as The History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents. Three different printers printed the book in London: E. Cotes for G. Sawbridge at the Bible on Ludgate Hill, T. Williams at the Bible in Little Britain and T. Johnson at the Key in Paul’s Churchyard – once again all based around the previously mentioned printers’ area near St Paul’s Cathedral. Topsel’s books were famous for their amazing images, which are obviously based on fantasy and imagination.

One dragon in particular, the dragon statue at Temple Bar, is also referenced in more modern publications. The first to mention the Temple Bar dragon was Virginia Woolf in 1947, in her book The Years. We find the same beast featured in Stoneheart by Charlie Fletcher, a children’s book about the adventures of a young boy in London published more recently, in 2006.

A legged, wingless dragon

Imagine travelling back to the 16th century. While walking the streets of your city, all of a sudden you notice a giant dragon obstructing your way. You have never seen one before but have heard about these beasts via word of mouth. What would you do?! In fact, this is the fantastical account of a real episode, according to Italian naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi. On the 13th May 1572, such a beast supposedly really was roaming the Bologna landscape. Some citizens managed to capture it, and promptly displayed it in a museum (one of the very first museums in the world, in fact: Bologna’s Aldrovandi museum).

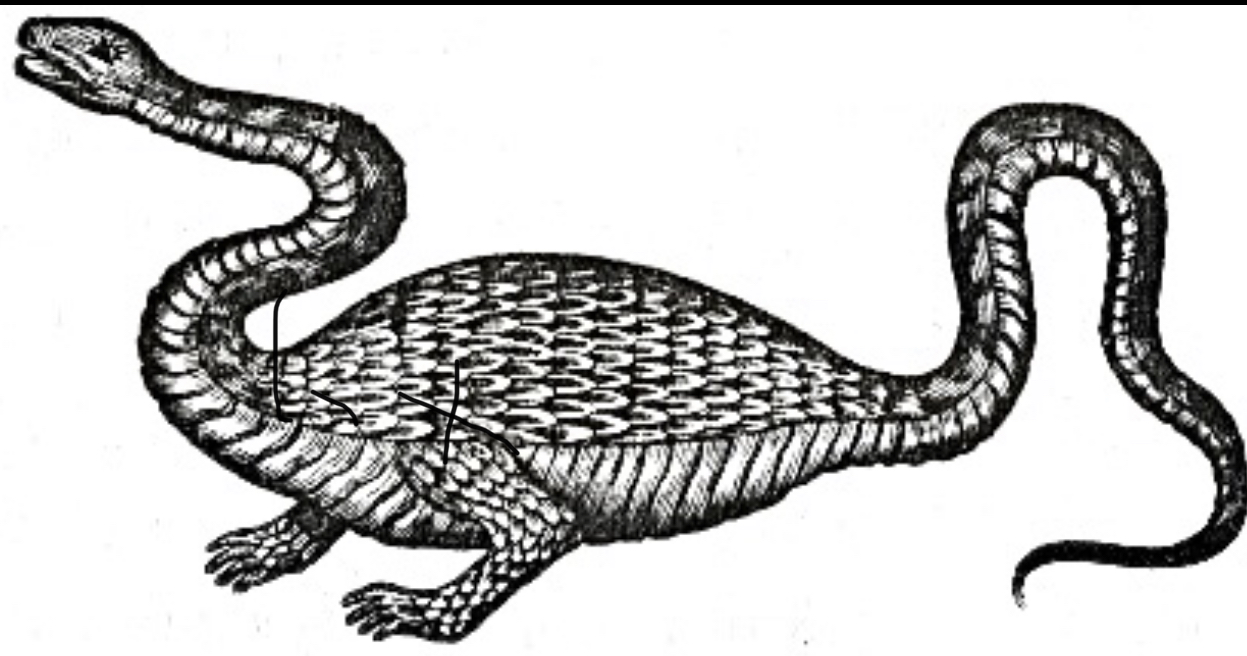

In Aldrovandi’s book Serpentum et draconum historiae libri duo (History of Snakes and Dragons in Two Books) he offers two images of the dragons, one in black and white and one in colour. The description under the images reads ‘Draco bipes apteros captus in Agro Bononiensi‘, meaning ‘Dragon legged wingless captured in the countryside of Bologna’.

Some questions are not explained – such as how this creature managed to find itself in the vicinity of a developed city such as Bologna in 1572. Consider also that this city was already the site of the oldest university in the world, having been founded in 1088. With this in mind, one would have thought there should have been quite a few people educated enough to understand the real nature of this ‘dragon’ without misunderstanding it for a fantastic beast.

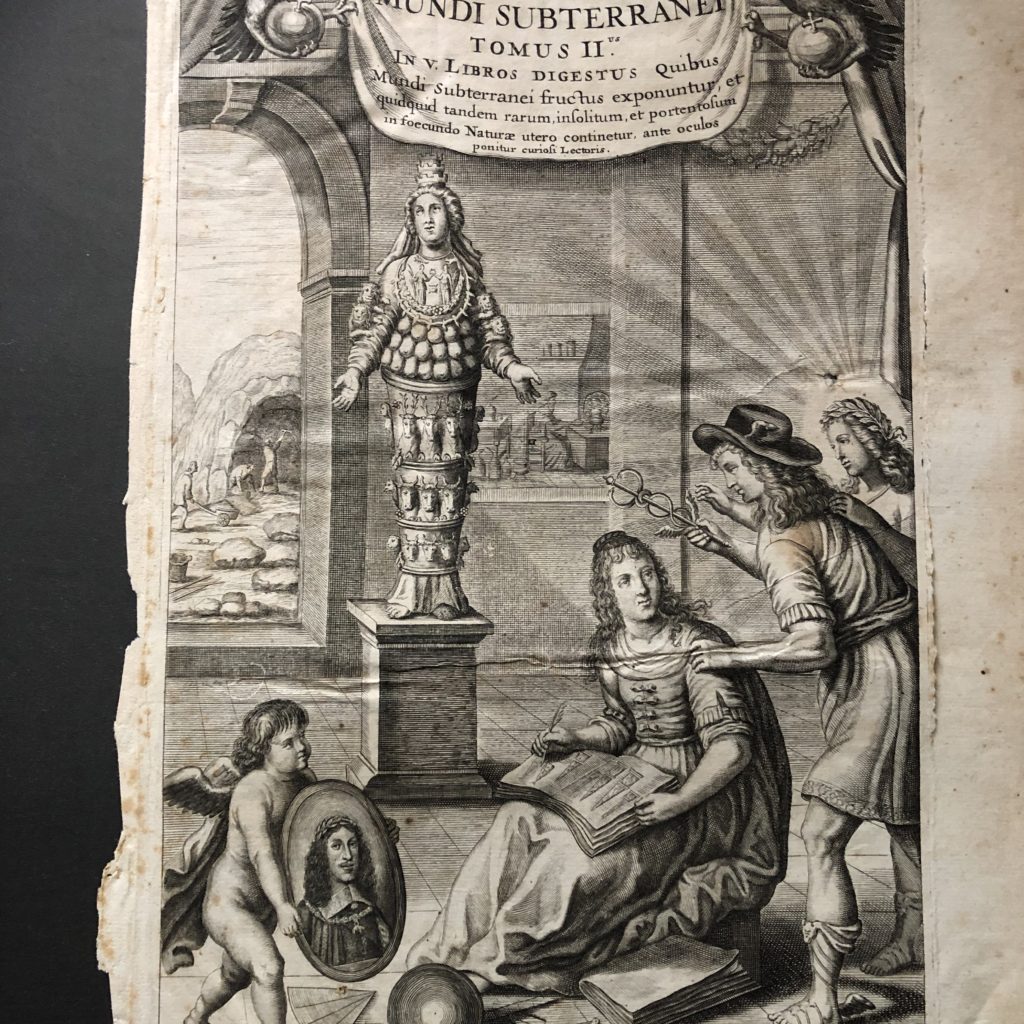

The above-mentioned dragon was also illustrated in Athanasius Kircher’s 1665 book Mundus subterraneus (‘The Underground World’) for readers – and all posterity – to admire. In this book, the German-born Jesuit priest and scientist describes all the creatures and atmospheres allegedly populating the underground of our planet.

With the knowledge and differing attitude of humans towards these sorts of phenomena, we might have a different response to this ‘dragon’ today. In fact, scientists investigating the image in the Kircher’s book now believe that it may have been based on an animal similar to a toad or snake.

It is likely that even Aldrovandi was aware that it was not a real dragon, but that he wanted to deliberately rouse even more curiosity in order to attract a larger number of visitors to his museum. Seen and analysed with a 21st century mind we can say that it might not have been, perhaps, a real dragon. It does however illustrate that in the 16th century, dragons were a popular subject just about everywhere.

Dragons, Western Mythology and Arthurian Legend

In Western mythology the dragon was often an evil beast. The returning Crusaders told us the extremely popular story of Saint George and the Dragon, but we should also mention here the legend of a woman fighting a dragon: Martha of Bethany, the sister of Lazarus and Mary. While in Tarascon in southern France, Martha heard of a dragon frightening the inhabitants every day. In order to help the worried population, she decided to bless the dragon with a sprinkle of holy water while keeping it at a distance with the power given by a holy cross. She managed to capture the dragon with her belt, and it was then paraded through the village.

Another example is Margaret of Antioch, who was asked by a Roman Governor to marry him and to renounce to her Christian belief. She refused him, and was brutally tortured and tempted by the devil disguised as a dragon. When eaten by the dragon Margaret managed to escape from the inside of the monster, helped by the holy cross she was holding.

Historically around Europe, dragons (together with other animals, colours, and symbols) were regularly used in the battlefields, depicted on banners. This was done in order to distinguish between different parties, and these signs reproduced on shields and flags thus encouraged the emergence of heraldry – especially in Britain, influenced by the Romans armies in the past.

Today, the red dragon is still the most famous symbol of Wales and its use as a national symbol goes back through folklore, Arthurian legends, and the arrival of the Romans in London and subsequent rapid expansion on our island, as represented in many books and images. In fact, the dragon has a long tradition with Wales and has been associated with this land since Owain ap Mareddud ap Tudur (then anglicised as Sir Owen Tudor), the grandfather of Henry VII and founder of the Tudor dynasty.

Sir Owen Tudor claimed descent from Cadwaladr, and used a red dragon emblem. When Henry Tudor arrived in Wales in 1485, he reclaimed the red dragon because of part of a prophecy made by the great wizard Merlin as recounted by Geoffrey of Monmouth in his book Prophetiae Merlini, also known as Libellus Merlini.

Very briefly, the prophecy is related to Vortigen (which can be spelt in varying similar ways), a 5th century British warlord in Britain also allegedly known also as the king of the Britons, who asked Ambrosius (Merlin) about a vision he had of two dragons, one white and one red, fighting. Ambrosius answered that the white represented the Saxons, who would be victorious over the red, signifying the British.

Geoffrey of Monmouth also mentioned the vision of this battle of two dragons later in another of his writings, titled Historia Regum Britanniae. Allegedly handwritten around 1136, Monmouth frequently mentions London inthis book as a place where pre-Arthurian kings used to gather. King Arthur and his father Uther Pendragon used to meet frequently in London.

We notice in the prose Lancelot that, more than three times, the meeting point for King Arthur is London. We all know of the friendship between King Arthur and the dragons who helped him in his legendary battles. He also received the mythical sword Excalibur by the enchantress and sorceress Morgana. She was secretly hoping that Arthur would kill the dragons with this weapon, until Merlin revealed her as an evil sorceress. The only person able to use Excalibur’s full potential was Merlin.

Other Literary Dragons

An early literary mention of dragons can be found in a book written by the alchemist Nicholas Flamel, titled Le Livre des figures hiéroglyphiques or The Book of Hieroglyphic Figures. First published in Paris in 1612 as part of Trois traictez de la philosophie naturelle (Three Treatises of Natural Philosophy, it was translated in 1624 and later printed in London by Thomas Snodham for Thomas Walkley. The third chapter of this book is nearly entirely devoted to the description of two dragons, the first ‘called Sulphur, or heat and dryness, and the latter Argent Vive, or cold and moisture’.

Flamel’s description continues: ‘These are the Serpents and Dragons which the ancient Egyptians have painted in a circle, the head biting the tail’. Here, we have a clear reference to the Ouroboros, the famous alchemical symbol of a snake or a dragon biting its own tail.

The Ouroboros most likely originated in ancient Egypt, and because of its configuration, it is seen as a representation of the eternal cycle of life and was used in this way in alchemy. Flamel writes that ‘These are they upon whom Jason in his adventure for the Golden Fleece, powered the broth or liquor prepared by the fair Medea, of the discourse of whom the Books of the Philosophers are so full, that there is no philosopher that ever was, but he has written of it, from the time of the truth telling Hermes Trismegistus, Orpheus, Morienus, and the other following, even unto myself‘.

Especially in the last section of this phrase, and with the extremely important names mentioned, we have a straight reference in Flamel’s book to dragons and the transmutation of element and metals.

Another important literary mention is in the poem Beowulf. In the actual epic, Beowulf’s battle with the dragon also represents the eternal battle between good and evil, and ends in the deaths of both the dragon and Beowulf himself.

The Dragons of 21st Century London

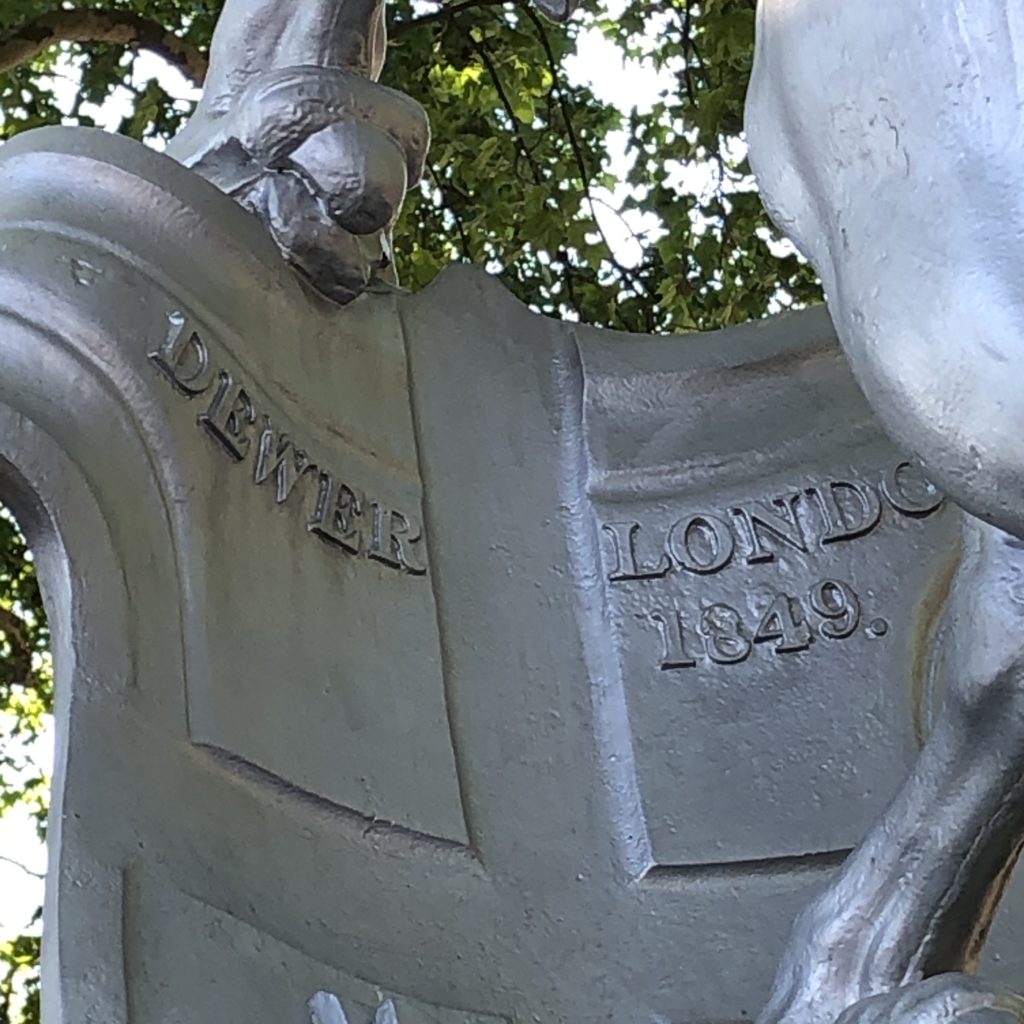

As we have seen, history is full of these dragons – but we can still see them today. The most remarkable example is in the City of London, where dragons have been guarding the City’s boundaries since 1849.

They hold a shield with the City of London coat of arms. The first couple of dragons were erected outside the entrance of the now (unfortunately) demolished Coal Exchange on Lower Thames Street. Once removed from their original location in 1964, they were placed in Temple Gardens by Victoria Embankment.

The dragons’ design was so successful with the Corporation of London’s Street Committee that they became the preferred model for new dragons to mark the boundaries of London, replacing the oldest, which has been atop the memorial pedestal in Temple Bar since 1880.

The dragons guarding the City of London are thirteen in total, and are placed where seven original gate entrances used to stand in the old times.

According to the majority of sources, they symbolise the connection with St. George’s killing of the dragon. In addition, any dragon if represented with its tail knotted, symbolises victory over the powers of malevolent and heretical doctrine. As with symbolic literary references, depictions of a dragon were usually in this form of ‘the serpent and the bird’ to symbolise, respectively, evil and goodness.

It is quite strange to notice that amongst all of the descriptions in the many texts and contexts we have explored, we do not seem to have even one dragon that completely matches another. They are all different! None of the essayists and studies that I have read and researched were able to explain why, but perhaps the next time you are walking in the City of London, you’ll think a little more about the dragons that are surrounding and protecting you.

Find out more:

Fabrizio Selli is a London historian and archaeologist. He is based in London, where he collaborates with a few museums and enjoys the story of this unique city. He is interested in the history of alchemy, Shakespeare and his Folios and Dr. John Dee, but his main passion and obsession is the ‘frost fairs’ which used to be held on the frozen River Thames (and others).